Overview of Circadian Rhythms

Circadian rhythms are approximately 24 hour cycles that govern many physiological and behavioral processes in living beings. They are endogenous in origin, generated by internal clocks, yet they are entrained by environmental cues such as light and temperature. This topic spans biology, psychology, medicine, agriculture, and even computer science as researchers seek to understand how these clocks coordinate complex life systems.

Key Vocabulary

Endogenous clock, zeitgeber, entrainment, phase, amplitude, period, phase response curve, chronotype, suprachiasmatic nucleus, melatonin.

Historical Context

Early observations of daily cycles in behavior date back to ancient times, but the modern conception of circadian biology emerged in the 20th century with experiments in plants, fruit flies, and mammals showing genetic control of rhythmicity. The discovery of clock genes and feedback loops revealed a molecular basis for these rhythms and opened new avenues for treating jet lag, shift work disorder, and metabolic diseases.

Core Concepts

The central idea is that organisms carry an internal oscillator that cycles with a period near 24 hours. This oscillator can be influenced by external cues, called zeitgebers, which synchronize the clock to the environment. In mammals, the master clock resides in a brain region called the suprachiasmatic nucleus SCN, which receives light information from the retina and adjusts the clock by updating gene expression and neuronal activity.

Biological Mechanisms

At a molecular level a network of genes and proteins interacts in feedback loops to produce oscillations. Certain genes are transcribed in bursts, the resulting proteins accumulate, and upon reaching thresholds they inhibit their own transcription, creating a cycle. This architecture is robust yet flexible, allowing cells in different tissues to oscillate in synchrony or to display tissue specific phases.

Physiological and Behavioral Outputs

Rhythms influence sleep wake cycles, hormone release, body temperature, metabolism, and cognitive performance. Misalignment between internal clocks and the external world can result in fatigue, impaired metabolism, and mood disturbances, illustrating the health significance of reliable circadian timing.

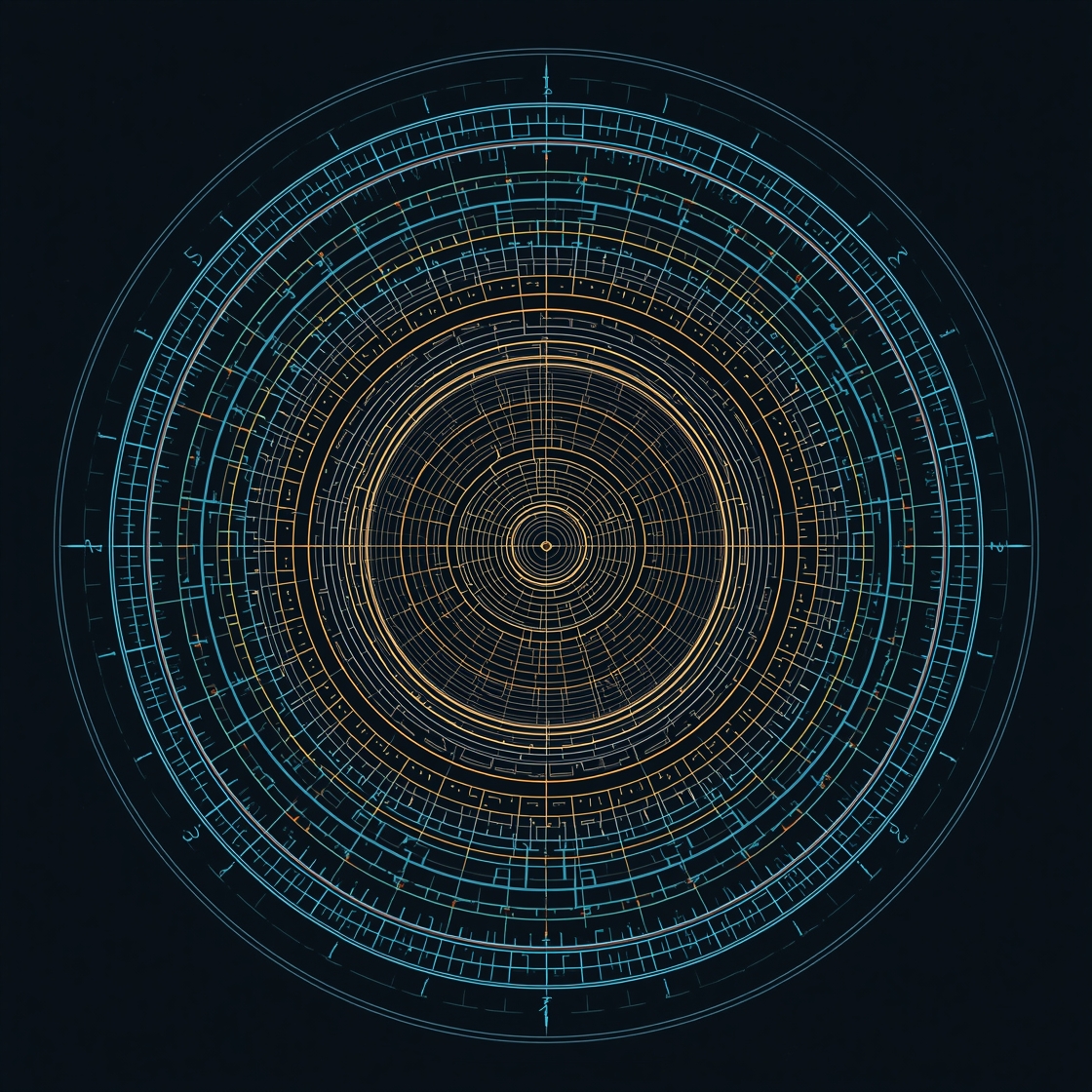

Mathematical Models and Quantitative Thinking

Scientists use a mix of qualitative descriptions and mathematical models to study circadian rhythms. Simple models describe cycles using sine waves with varying amplitude and period. More advanced models use delay differential equations, coupled oscillators, and phase response curves to predict how a clock adapts to light pulses or temperature shifts.

Simple Oscillator Concept

A basic way to imagine the clock is as a pendulum that continues to swing with a rhythm. In a real clock the period is not perfectly 24 hours but close enough to coordinate daily activities. The model helps students reason about how small changes in the environment can shift the timing of the cycle.

Phase Response Curve

The phase response curve describes how a stimulus at different times in the cycle shifts the phase of the clock. Light exposure early in the day might advance the clock while light exposure late at night might delay it. This framework helps explain jet lag and adaptation to shift work.

Applications and Implications

Understanding circadian rhythms has tangible outcomes for health, productivity, and agriculture. For instance, aligning work schedules with individual chronotypes can improve performance and reduce health risks. In medicine, timing of drug administration, a concept known as chronotherapy, can enhance efficacy and reduce side effects by exploiting natural rhythms in physiology.

Health and Medicine

Disruptions in circadian timing are associated with obesity, diabetes, cancer risk, and mood disorders. Treatments that restore proper timing, such as light therapy or melatonin administration, are used in clinical practice for sleep disorders and seasonal affective disorder. Personalized chronotherapy is an active area of research that tailors interventions to an individual's clock characteristics.

Agriculture and Ecology

Plant and animal rhythms influence growth, reproduction, and resilience to environmental stress. Understanding these rhythms can improve crop yields, pest management, and conservation strategies by aligning interventions with the natural timing of organisms.

Experiments and Evidence

Students can explore circadian phenomena through simple classroom demonstrations or at home. For example, monitoring alertness or reaction time across the day, tracking body temperature, or observing sleep patterns across a week can reveal daily rhythms. In laboratory settings, researchers study clock genes in model organisms to uncover how feedback loops generate cycles and how signaling pathways entrain clocks to light and temperature.

Ethical, Social, and Philosophical Considerations

As science reveals the universality of biological timing, ethical questions arise about the balancing of work, education, and health. Societal structures such as school start times and workplace shifts affect circadian alignment for large populations. Philosophically, circadian biology challenges our notion of free will and personal time management when biological processes exert predictable influences on behavior.

Questions for Reflection

Consider how internal clocks interact with external schedules in your daily life. Think about the design of school or work routines to support healthy circadian timing. Analyze a scenario in which a person must adjust to a new time zone on a short timetable. Propose a plan that uses light exposure, sleep timing, and activity scheduling to minimize jet lag.

Problem Set

- Explain the difference between an endogenous oscillator and an environmental cue. Why is both necessary for stable circadian timing?

- Describe what a phase response curve tells us about how light affects clock timing. Give an example of a shift in clock phase due to a light pulse.

- Propose a simple classroom activity to illustrate how a circadian rhythm can be entrained by a zeitgeber. Include measurements and data analysis steps.

- Discuss health implications of chronic circadian misalignment. What interventions are supported by evidence to mitigate these risks?

- Propose a hypothetical chronotherapy schedule for a patient taking a daily medication. Consider timing relative to their natural rhythm.

Conclusion

Circadian biology reveals a remarkable, interdisciplinary story about how life keeps time. From molecules inside cells to global public health policies, timing matters. By studying rhythms, students gain a framework for thinking critically about biology, medicine, and the design of human activities that respect our inner clocks.